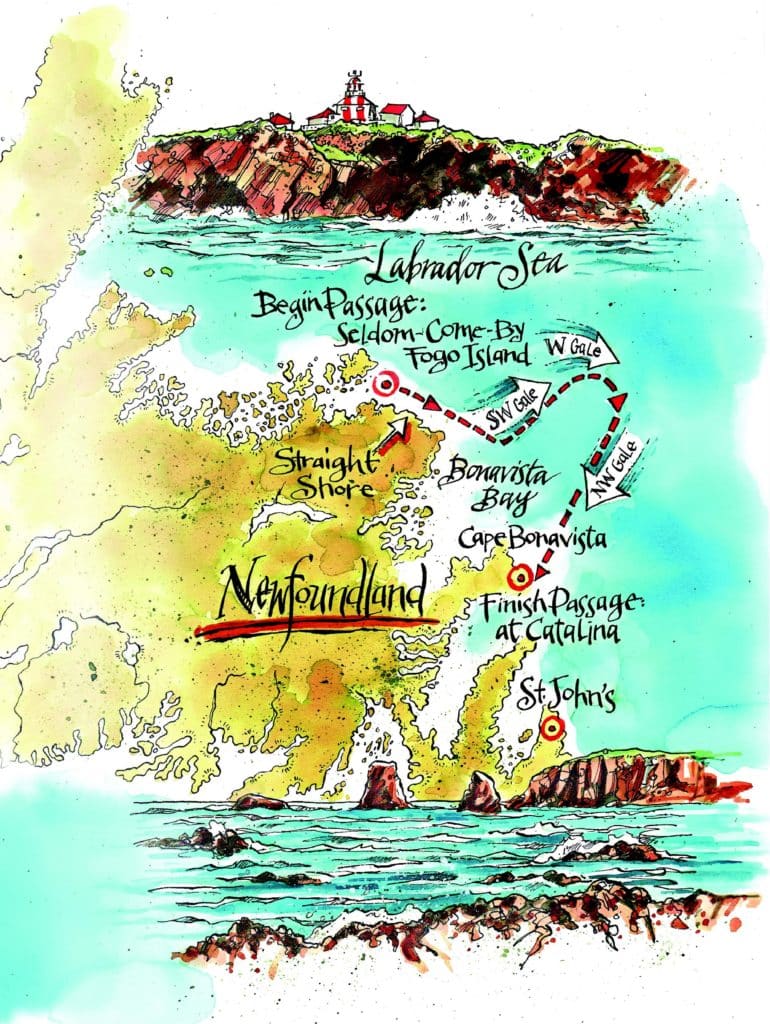

The west wind rattles in the rigging, rolling Brendan’s Isle, my 50-foot FD-12 cutter, against the pier at Seldom-Come-By, where she’s moored. The sky above Fogo Island is filled with mares’ tails. I’m awake before sunrise and seated at the navigator’s station, where I pore over a stack of navigational charts. The feature on these charts that dominates my attention is a treacherous 40-mile section of coast that lies to the east and south of our present location: the infamous Straight Shore of Newfoundland. The chart shows no safe harbors along this shore. The off-lying banks are dotted with low, reef-strewn islands. The waters close to the beach are shoal and filled with uncharted rocks. And just beyond Cape Freels, at the far eastern end of the strand, lies an area of shallow ledges and unpredictable currents so foul and uninviting that it’s earned an equally foul and uninviting name from local mariners: the Stinking Banks.

The winds for the past several days have been light. The latest weather forecast, however, calls for increasing westerlies, strengthening to southwest 25 to 30 knots by midday, then strengthening again and increasing to southwest gales of 35 to 40 knots by afternoon. Ordinarily, such a forecast would be ample cause for a sailboat like ours to remain in harbor for the rest of the day, tucked up under the lee of the land and moored securely to a strong pier. But on this particular morning, the forecast gales seem an advantage rather than a threat, for if the forecasters are correct, the wind will blow directly off the land, transforming the Straight Shore into a sheltered area of slight seas and fast, dry sailing for its entire length.

As soon as breakfast is cleared away and the morning chores completed, my four young shipmates — Amanda, Liz, Nat, and Richard — and I cast off the mooring lines and point our boat’s bow seaward, heading south and east toward the Straight Shore and the bays of southeastern Newfoundland. For the first six hours of this passage, the weather conditions develop almost exactly as the forecasters have predicted, and my decision to sail seems a good one. The day is clear, and the wind, gusting across the land, is warm. All this begins to change, though, as soon as Brendan’s Isle sails clear of Cape Freels and enters the area of shoal water that extends for nearly 10 miles to the east.

Here, at the gaping mouth of Bonavista Bay, the wind accelerates along the shore, gusting above forecast velocities. The air and water temps plummet as the boat draws away from the land, and soon a cold fog materializes, seemingly out of nowhere, and obscures the horizon and limits the visibility to less than a mile.

Earlier in the day, while Brendan’s Isle was still sailing under the lee of the Straight Shore, I’d asked Amanda and Richard to help me reduce the rig to a fully reefed mainsail and spitfire jib. But now, even this small amount of sail begins to overpower the boat in the gusts that have swirled up out of the gloom. I take over the helm as we draw abeam of the whistle buoy at Charge Rock, and I struggle to drive the boat a few more degrees to windward. Just over two miles ahead are the Stinking Banks. To the west and south of these is Bonavista Bay itself, with dozens of safe harbors at Valleyfield, Indian Bay, Lockers Bay, and a maze of islands and thoroughfares beyond.

For an hour I battle with the helm. Unwilling to admit that I’ve made a mistake in ignoring the morning’s forecast, I try to force the sailboat into breaking seas and keep her head to wind, but she won’t respond. She heels over, spilling the wind out of her sails and making more leeway than headway. The Stinking Banks remain an obstacle that she can’t surmount.

“I get the feeling that we might be spending the night out here!” hollers Amanda, her voice distorted by the wind as the boat hobbyhorses across crooked seas.

“Might be better than breaking the rig!” cries Nat.

“Or breaking ourselves,” I mutter, realizing that the only sensible alternative at this point is to place the boat in a defensive attitude and wait out the gale in the mouth of Bonavista Bay.

Deteriorating Conditions

In a gale at sea, a sailor must learn how to move in concert with the forces arrayed against the boat. As the wind increases and the seas grow more chaotic, he or she must discover how to set aside personal desires and surrender to the agenda that nature has prepared, seeking a safe compromise with the conditions at hand.

Some sailboats manage best under such conditions when they’re brought head to wind with a drogue or sea anchor fastened to the bow. Others ride most comfortably when they’re left to lie ahull, drifting on their own in the trough of the swell with all the sails removed. And still others are best served when they’re allowed to run off, powered by a tiny patch of sail to maintain steerage and dragging warps from astern, if necessary, to keep from running too fast down breaking seas and tripping over the bow.

Once I decide to stop fighting the wind, I have little doubt about which of these tactics will serve best, for Brendan’s Isle can ride to a following sea better than any I’ve ever sailed. I ask Nat to steer downwind and put the seas on the quarter while Amanda and I rig the storm trysail. Right away, the boat stops laboring. The spray that had been driving across the bows abruptly ceases. The noise of the wind drops. The crash of waves sluicing down the decks is replaced by the hissing sound of water flowing past the taffrail. Even without warps, the boat settles into a comfortable rhythm. With almost no effort on the helm, she moves off on an easy reach, slipping down the backs of seas to make her way south and east.

Waiting Games

The next 12 hours serve as a break in the progression of the journey — a hiatus in which there’s nothing else to do but hunker down and wait for the gale to moderate. Beginning with Nat, each member of the crew agrees to take an hour’s trick at the helm. Off watch, I remain below, on call in case of emergency but otherwise banished to the solitude of the cabins and the safety of my own bunk. For hour after hour I lie pinned against the leeboard, serenaded by the creak of the steering cable and the rush of water along the hull and confined to the company of my own thoughts.

For a time I entertain myself with a game I’d devised during other nights at sea when the swell was just as large and the noise of the wind just as shrill. The object is to make sense of the cacophony of thumps, creaks, and groans that the boat makes as she rolls across a deep seaway. First I create a mental inventory of all the sounds, ordering them from loudest to quietest. Ten I attach an appropriate description to each sound — a cockpit scupper clearing its drain, a squeaking bulkhead where an old glue joint has failed, a glass bottle shifting position in one of the galley cupboards, a halyard slapping against the mast, a bilge pump cycling on and off. Each time that I find a satisfactory description, I remove the sound in question from the general inventory and store it away in a kind of imaginary recycle bin. In this way, I’m able to eliminate sound after sound until — in my imagination, at any rate — both the boat and the sea beyond become dead quiet.

On this particular evening, with Brendan’s Isle reefed down and running off in the approach to Bonavista Bay, I’m able to find a name for every sound I hear. Now I can close my eyes, breathe deeply, and let myself drift in and out of a kind of semidream state, confident — at least until the advent of some jarring new sound — that my young shipmate at the helm has the sailboat under control.

The sound game, of course, hasn’t always proven so successful. Fifteen years ago, during the first transatlantic crossing that Brendan’s Isle made, the boat was new and unfamiliar to those of us who sailed her — which meant that many of the sounds she made were still difficult to decipher. A clanking noise I’d never heard before would nearly drive me crazy until I’d risen from my bunk to search it out. The sound would usually be benign, but sometimes, often right about the time I’d decided that I could ignore it, it would prove to be the signal of a crisis in the making: a broken linkage on the steering vane, perhaps, or a loose drive wheel on the refrigerator’s compressor pump.

Another source of worry on some of the early passages was that the new rig and gear were still untested under extreme conditions. Twice on that first Atlantic crossing I was awakened from a deep sleep to crashing noises on deck. The first time, when we were six days out of Chesapeake Bay and on the southern edge of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, I awoke to an explosion that sounded like a cannon’s report. This was followed immediately by a sudden deceleration in the boat’s forward momentum and a muffled cry from the cockpit. The first thing I noticed, as I scurried up the companionway steps, was the torn head of the spinnaker flying at the masthead like the tattered banner of some defeated regiment. The rest of the sail had been shredded into several long streamers now being dragged along the hull to leeward just beneath the surface of the water.

The second crashing noise occurred several hundred miles south of Iceland, during a sequence of gales that had stalked our cutter for 12 uninterrupted days. Brendan’s Isle was running that afternoon in near-gale conditions under a triple-reefed mainsail and a yankee jib poled out to windward on an aluminum reaching pole. I was sleeping soundly when the whole vessel began to jump in time to a series of concussions that sounded like someone trying to stove in the foredeck with a pile driver.

I stumbled out of my bunk, pulling on boots and safety harness, and groped in the darkness toward the companionway steps. Up on deck, the two watch keepers seemed stunned, their jaws agape, as they stared at a broken section of the reaching pole spinning drunkenly from its attachment point at the clew of the yankee. Each time the sailboat accelerated down a wave, the pole — or what was left of it — made a complete rotation, driving its jagged end into the teak deck and sending chips of splintered wood into the air. One section of the pole hung limply against the mast, banging metal on metal with a rhythmic clank, while the other end spun like the blade of a wounded helicopter, defying anyone to go forward to try to wrestle it down to the deck.

The crisis, thankfully, was resolved without incident, and it didn’t deter the successful completion of the voyage. It taught a lesson, however, as every emergency at sea is likely to do. The pole was strengthened with a heavier extrusion and better end fittings as soon as we found a good machine shop in Europe.

With these oddly comforting thoughts, I let my mind come back into the present moment, with Brendan’s Isle running off and moving easily in the mouth of Bonavista Bay. I roll over in my bunk and feel myself beginning to doze off, transported into an almost euphoric sense of well-being by the now-familiar sounds of our sturdy little vessel as she skids down the backs of following seas.

New day, New direction

Shortly after midnight, the fog begins to lift, and the wind veers into the northwest. Richard calls from the helm into the open window above my bunk, explaining that he’s just spotted a light flashing on the horizon far off to starboard. I pull on my boots and foul-weather jacket and mount the steps into the cockpit. The wind still whines in the rigging, and the seas remain steep and unruly, but the air has turned colder, and a gibbous moon has emerged from behind ragged clouds to light the decks with an eerie silver glow. The flashing light on the horizon, I know, is the lighthouse at Cape Bonavista, a bold headland that marks the boundary between Bonavista Bay, to the north, and Trinity Bay, to the south. If we bear off, I tell Richard, keeping the wind on our quarter and the lighthouse on our starboard bow, we should close with the cape by sunrise. Then, with luck, we might fetch up under its lee and find safe harbor somewhere along the Trinity shore.

The night advances through the setting of the moon and the rotation of the Big Dipper around the North Star. Amanda follows Richard at the helm. Liz follows Amanda. The dawn creeps into the eastern sky, and the shape of the land grows on the horizon. The wind eases back as the sailboat doubles Cape Bonavista, then eases again as she passes a series of small headlands at Spillars Point, Flowers Point, and North Head. Finally, as she draws abreast of a fairway buoy at Poor Shoal, the high land to the north closes in behind her, and the wind drops in earnest.

To the east, a trio of humpback whales roll in lazy circles. To the west, a set of range lights marks the entrance to Catalina harbor, a landlocked bay that provides the most secure anchorage on this coast for a dozen miles in either direction. I fire up the diesel engine and follow a fishing boat into a buoyed channel that leads between a pair of rocky headlands and up to a small village. I hardly notice the men who stand clustered on the government pier or the rafts of fishing vessels moored on either side, so eager am I to conclude this long and difficult night. I simply guide the sailboat into an empty berth, make a cursory check of the mooring lines, and head below for a few delicious hours of deep and dreamless sleep.

The U.S. Coast Guard is asking all boat owners and operators to help reduce fatalities, injuries, property damage, and associated healthcare costs related to recreational boating accidents by taking personal responsibility for their own safety and the safety of their passengers. Essential steps include: wearing a life jacket at all times and requiring passengers to do the same; never boating under the influence (BUI); successfully completing a boating safety course; and getting a Vessel Safety Check (VSC) annually from local U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, United States Power Squadrons(r), or your state boating agency’s Vessel Examiners. The U.S. Coast Guard reminds all boaters to “Boat Responsibly!” For more tips on boating safety, visit www.uscgboating.org.