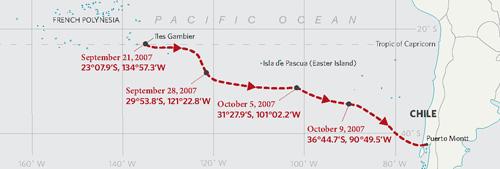

At the end of September 2007, my husband, Evans Starzinger, and I were in the Îles Gambier, at the southeastern edge of French Polynesia, aboard our 47-foot aluminum Van de Stadt Samoa, Hawk. We were about to embark upon a 3,400-nautical-mile passage to Canal de Chacao, the narrow channel that leads to Puerto Montt, at the north end of the channels in Chile.

The passage would take us across three of the global wind systems: the southeast trades, the variables, and the westerlies of the Roaring 40s. During what turned out to be a 24-day (and 3,800-nautical-miles-sailed) passage, we relied upon the weather information derived from Gridded Binary Files to help us pick our way through the complex weather systems we encountered. By sharing the exact information we had at our disposal, we hope to help others understand these valuable forecasting tools and how we make use of them to benefit from or avoid weather systems.

The Îles Gambier are located in the belt of southeast trade winds that extends to around 30 degrees S. To avoid beating dead into the trade winds for several hundred miles, the traditional sailing route between French Polynesia and the Chilean coast calls for vessels to sail as close to due south as they can manage through the southeast trades and the variables until reaching the westerlies of the Roaring 40s. Here, voyagers turn east and run to Chile.

To avoid being becalmed in the Southern Hemisphere summer (December through February), vessels may need to drop below 45 degrees S to remain in the westerly flow of winds under the semi-permanent high-pressure system centered around 30 degrees S, in the vicinity of Easter Island. In the early Southern Hemisphere spring, when we were about to embark, the South Pacific high would be expected to be north of its summer position and not yet fully established. Low-pressure systems with strong westerly flows would be tracking as far north as 30 degrees S, which we hoped would allow us to sail more directly to our destination.

When departing on a long passage, we start with the assumption that we will follow the conventional sailing directions, but two weeks before our departure we start watching how systems are actually tracking and whether we should modify our route. Because we were coming to the end of the trade-wind season, low-pressure systems had begun tracking across the Gambiers from the north and west, out of the subtropics, pushing easterly winds ahead of them. Since the South Pacific high wasn’t yet established, both lows and highs from the Roaring 40s regularly rolled northward into the variables; these, too, brought easterly winds well above 35 S. Taking the traditional route with these weather patterns would mean many days of beating into easterlies and the likelihood of several easterly gales or even storms. By mid-September and our departure, it was becoming increasingly apparent that we’d have to modify the traditional route to avoid a significant percentage of strong headwinds.

During this passage, we’d download GRIBs once a day. When determining where we’d be on each successive time period in the GRIBs, we assumed an average of 150 nautical miles per day.

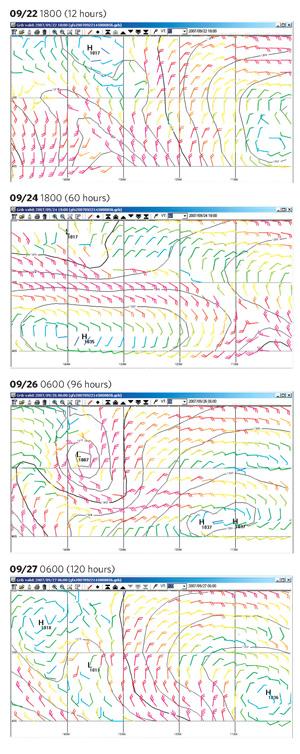

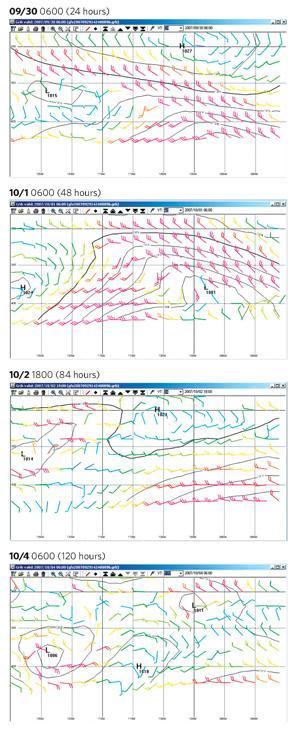

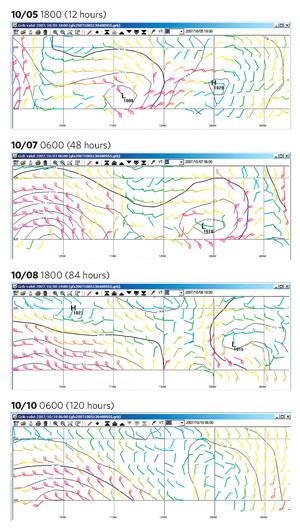

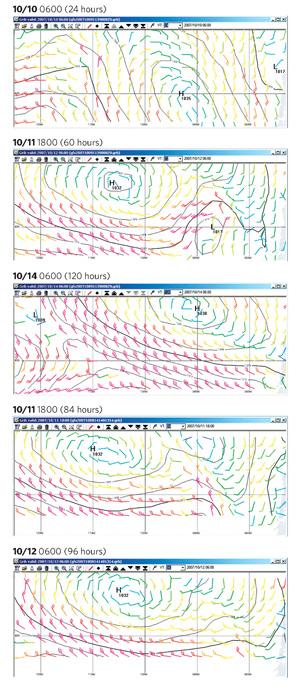

Here’s a look at four 120-hour GRIB files we downloaded during our trip, how we interpreted them, and how the actual weather systems played out.

For much of this passage, we felt like a pinball ricocheting between the various low-pressure and high-pressure systems, but by using the GRIBs, we never experienced sustained winds of more than 40 knots or headwinds of more than 20 knots true. Few passages are this complicated, and those that are rarely work out so well. But in this case, the GRIBs made for a much easier passage than we would’ve had if we’d followed the conventional sailing route.

Hawk’s Route

About GRIBS and forecasting

>> Reliability of the GRIBs: GRIB files are raw data plucked from national oceanic and Atmospheric Administration databases without human interpretation. As unedited raw data, they require analysis by the user. though the models have improved in the decade that we’ve been using them, the forecasts diverge from reality at least half the time in the periods between 72 and 96 hours. We heavily weight the first 48 hours and tend to discount the last 48 hours unless the systems shown are large and well defined.

>> North/south passages vs. east/west passages: We’ve found the GRIBs to be most useful on passages in the temperate and high latitudes that have a large north/south component, like the one described in this article, and less useful on downwind passages made within a degree or so of the same latitude. that’s because when running down the latitude, large systems overtake the vessel from behind with generally following winds, making it less necessary and less useful to maneuver a bit north or south as a system approaches. When sailing north/south, the crew has many more options and can choose a course 90 degrees from the route while still making progress toward the destination, which is enough to maneuver with respect to smaller systems. Also, headwinds are much more likely on these north/south routes, and small changes in position, as in the final example in this article, can position the vessel to avoid them.** **

>> Wind speeds: The GRIBs forecast average sustained winds, which means that gusts can easily be 20 percent to 30 percent higher. In gales and storms, we tend to set the boat up to handle the gusts, so when looking at wind speeds around storm systems, we add 5 to 10 knots to the forecast wind speed when deciding what sails to carry or how closely we should approach the low center.

>> Small, compact systems: The GRIBs shown in this article use a reporting area based on a latitude/longitude grid with 5 degrees on an edge. these can fail to show small, compact, and intense systems such as meteorological bombs or tropical depressions. GRIBs can be downloaded with a resolution of 1 degree on an edge but even then may not capture these dangerous systems. Throughout this passage, we were also downloading text weather forecasts off our Inmarsat-C for the next 24 hours, and those would’ve warned us of something small but intense that the GRIBs might miss.

>> Timing of weather systems: When the GRIBs get things wrong in the first 24 hours, it’s almost always because systems have moved faster or slower than forecast or have moved slightly north or south of their forecast track. This was the case with our October 5 forecast, when the low-pressure system came right over the top of us instead of staying south. By tracking changes in the wind direction, cloud cover, and barometric pressure, we can tell where we are with respect to an approaching system, and we can tell when the system passes over us — even if it’s significantly before or after the GRIBs had forecast. This is one of the main reasons why we download the barometric pressure as part of the GRIBs, though it makes for a larger file and costs more to download. With this information, we can easily tell how close we are to the center of a system and how quickly it’s moving using our barometer.****

>> “Mushy” weather patterns: Strong, well-defined systems tend to develop as forecast. But when many weak, poorly defined systems and slack areas of little wind cover the forecasting area, we don’t place much confidence in the forecast. In our experience, one system will almost always begin to dominate and drive things in a different direction than the GRIBs are forecasting. In these situations, we often download GRIBS every 12 hours to see if anything is developing.

>> Margin of error: Part of our decision-making is based on what will give us the greatest margin of error and keep the most options open should the end of the GRIB forecast period be way off. When passing close to the center of a low-pressure system, we tend to aim for a band of 20-knot winds so that if the system moves closer to us, we’ll still be out of the strongest winds. In my last example, we chose to stay on the back of the low in case another low should follow in its track — which is exactly what happened. If we hadn’t done that, we would’ve been pinned on the Chilean coast in a strong southerly flow facing a major beat against wind and current to reach the Canal de Chacao.

Anchored at Mangareva, Îles Gambier

September 21 23°07.9’S, 134°57.3’W

>> Synopsis: A large area of very light to no wind surrounds a weak high-pressure system (with a center pressure of 1017 millibars) over the Îles Gambier. (See 09/22 1800 (12 hours).) this persists until September 24 with the approach of a weak low-pressure system (center pressure 1017 millibars) moving southeast over the top of a strong high-pressure system (center pressure 1035 millibars) well to the south of the island. (See 09/24 1800 (60 hours).) These two systems form an extensive easterly flow as far north as 27 degrees S, less than 250 miles due south of the island. The high (center pressure 1037 millibars) continues to move east as the deepening low (center pressure 1007 millibars) pushes south, creating a squash zone between the two with easterly winds of at least 30 knots south of the island and a large band of moderate to strong north-to-northeast winds to the east of the island. (See 09/26 0600 (96 hours).) As the high (center pressure 1036 millibars) moves off to the east, the low (center pressure 1013) starts to fill, and another weak high (center pressure 1018 millibars) approaches the Gambiers. (See 09/27 0600 (120 hours).) the northeasterly flow persists to the northwest of the more southerly high-pressure system until the end of the forecast period, when the high is predicted to be centered around 46 degrees S, 103 degrees W.

>> Analysis: Except for strong southeast trades, this is the only other pattern we’ve been seeing for the past two weeks, and we can’t expect anything different to develop in the immediate future. Because the low passes to the west of the island moving from northwest to southeast and the strongest winds develop in the squash zone between the low and the high to the south of it, the system won’t bring us any westerly winds, and no favorable weather pattern develops for the entirety of the forecast period. Leaving the island in the light winds of the high and heading south would mean sailing directly into the strong easterly flow north of the high-pressure system in less than two days. If the low changes direction or strengthens even slightly, we could easily end up with gale-force east winds. While there are no more easterly winds below 25 degrees S in the forecast period, given the prevalence of easterly winds as far north as 30 degrees S over the past two weeks, we don’t want to run due south in the northerly flow trying to get to the westerlies on the back side of the high-pressure system and risk ending up in the path of another easterly gale.

>> Strategy: Rather than wait for the next weather pattern to develop in another 10 days, we decide to take advantage of the calm period to motor 200 miles due east of the island before the northerly winds from the approaching low fill in. If we can get east of 131 degrees W by the afternoon of September 24, we believe that we’ll be in a lighter, 15- to 20-knot band of northeast winds as the low moves from north to south. We could then turn southeast and sail on a close reach in the northerly flow from the high-pressure system through the end of the forecast period without going too far south until we see what winds the next set of systems are supposed to bring.

>> Actual: We’re able to sail for the first 12 hours, after which the wind drops to 2 to 3 knots. From there, we motor due east, reaching 23 degrees S, 131 degrees W on the afternoon of September 23. At that point, we turn off the engine, sheet in the main, lock the wheel, and wait for the northeast wind to fill in. By the early hours of September 24, we’re sailing close-hauled in light winds, and we spend much of the next four days sailing along at 40 to 50 degrees apparent, with 20 to 25 knots of apparent wind on a course of approximately 110 degrees magnetic, before the wind shifts to the north.

September 28, 29°53.8’S, 121°22.8’W

>> Synopsis: As the high-pressure system (center pressure 1029 millibars) moves farther north and east, the northerly winds will drop to 10 knots in the next 24 hours. (See 09/30 0600 (24 hours).) A low-pressure system (center pressure 1015 millibars) will approach from the west. this will bring a nice band of moderate northwest

winds along 30 degrees S, with gale-force winds between 30 degrees and 35 degrees S over the next 36 hours. (See 10/01 0600 (48 hours).) After that, a high-pressure system (center pressure 1023 millibars) is forecast to bring light and variable winds to the entire area between 30 degrees and 40 degrees S, followed by a weak low-pressure system (center pressure 1014) that continues the westerly flow around 30 degrees S. (See 10/02 1800 (84 hours).) The forecast period ends with a confusion of weak systems and the possibility of winds from just about any direction. (See 10/04 0600 (120 hours).)

>> Analysis: While the GRIBs have been consistent in their forecasts for September 28 through October 3, with two relatively strong and well-defined systems bringing a good band of westerly wind to the area centered around 30 degrees S, the remainder of the forecast has been changing daily for the past five days. The current version shows a large area of light and variable winds starting late on October 1, but most of the GRIBs over the past few days have shown a narrow band of westerly winds of 10 to 15 knots continuing along 30 degrees S. this forecast ends with what we call a “mushy” period, with many small, weak systems, any one of which could strengthen, displacing the rest. In this situation, we only really trust the first 48 hours or so of the forecast. Continuing southeast, along our current course, will put us right in the center of the next high-pressure system by October 2.

>> Strategy: We decide to turn due east along latitude 30 degrees S when the winds shift to the west, at least for the next 48 hours. We hope to stay in the band of 10- to 25-knot westerly winds along the top edge of the approaching low-pressure system. This should keep us out of the gale-force winds near the center of the low and north of the light winds at the center of the high pressure behind the low. Given the mushiness of the forecast at the end of the period, we’ll re-evaluate this strategy with each new forecast.

>> Actual: Over the course of the next six days, we stay within 30 miles of either side of 30 degrees S and manage to hold on to the westerly wind. We sail dead downwind in winds ranging from 8 to 25 knots true and motor during two periods for a total of about six hours when the wind falls below 5 knots true.

Just past our halfway point

October 5, 31°27.9’S, 101°02.2’W

>> Synopsis: We’ve started edging south in the band of northerly winds between a high to the southeast of us (center pressure 1028 millibars) and a low to the southwest (center pressure 1008 millibars). (See 10/05 1800 (12 hours).) As the low (center pressure 1010 millibars) continues to the west, it will bring a moderate band of westerly winds along our course, between 30 degrees S and 36 degrees S for 48 hours. (See 10/07 0600 (48 hours).) As it moves off, a high (center pressure 1023 millibars) approaches from northwest of our position and ridges down between the low moving away from us and the next low approaching from the west. this ridge will bring us light and variable winds while preventing the westerly winds from the next low-pressure system from actually reaching us. (See 10/10 0600 (120 hours).)

>> Analysis: We’re now a bit over halfway to Canal de Chacao, and we’ve made half of our easting, but we’ve only made about a third of our southing. We need to start working our way south, and we’d like to get south quickly enough to reach the band of 20-knot westerly winds just to the north of the low. once again, the forecast for the last three days of the period is very mushy and has been changing daily, so we’ll take the risk of ending up in the middle of the high-pressure ridge forecast to fill in October 10. We’ll see what develops after the low moves off and adjust our plans accordingly.

>> Strategy: Sail southeast along the great-circle course to Canal de Chacao (106 degrees magnetic). For the next 48 hours, expect northwest winds (shifting to the west) at less than 20 knots.

>> Actual: The weather we experienced wasn’t as forecast. the low moved more quickly north and east than expected, bringing us a frontal passage with northwest winds of more than 30 knots shifting to west and then southwest. Southwest winds of 20 to 25 knots lasted for another 24 hours, taking us through October 7. The actual weather gave us fast downwind sailing, and we made good 175 miles per day toward our destination on October 6 and 7. The low-pressure system then slowed, and we were able to make another 165 nautical miles in the southerly flow behind it on October 8.

October 9, 36°44.7’S, 90°49.5’W

>> Synopsis: As the low-pressure system (center pressure 1017 millibars) pulls away from us, we find ourselves in an increasing southeasterly flow from the leading edge of a high-pressure system (center pressure 1035 millibars) advancing from the south. (See 10/10 0600 (24 hours).) A low-pressure system (center pressure 1013 millibars) is forecast to come up out of the Southern ocean moving from southwest to northeast 48 hours later, creating a crush zone with a high-pressure system approaching from the west (center pressure 1032 millibars). (See 10/11 1800 (60 hours).) this low didn’t appear in any of the previous GRIBs , including the one from the day before. (Compare 10/11 1800 (84 hours) and 10/12 0600 (96 hours) for the same period from the GRIB of the day before.) After this low passes, a strong westerly flow fills in beneath the high-pressure system (center pressure 1030 millibars) that should carry us all the way to Canal de Chacao. (See 10/14 0600 (120 hours).)

>> Analysis: the low advancing out of the Southern ocean creates an ugly pattern. In the southeast winds before the low, we don’t have the option of sailing the great-circle course. We’ll be able to sail on starboard tack a bit north of east or on port tack a bit west of south. Sailing east will put us in the leading edge of the low with moderate south or southeast winds. It may also pin us against the coast with a strong southerly flow if another low follows the same track. Sailing south will put us onto the back of the low-pressure system with gale-force southwest winds, which will be just forward of the beam on the great-circle course to Canal de Chacao. In the last few days, the GRIBs have been showing a consistent southerly flow off the Chilean coast, where a current runs to the north. Beating down to Canal de Chacao against wind and current will be very difficult, so we want to avoid that possibility.

>> Strategy: Given the prevalence of southerly winds along the coast, we can’t afford to give up any southing. If this pattern holds and the low looks as if it really is going to develop in 24 hours, we’ll tack to the south even at the expense of losing some easting. this will get us south and give us greater flexibility to handle whatever might come next, but at the expense of making few miles toward our destination.

>> Actual: the southeast flow continues, and the GRIB on october 10 shows that we won’t be able to avoid the low. We tack to the south. In the next 24 hours, we sail 130 nautical miles and reach 38 degrees 30 minutes S, but only make good 10 miles toward our destination. By the early hours of October 12, we’re under staysail alone in southwest winds averaging 35 knots with gusts to 45 on a course just south of east with the wind just aft of the beam. Our strategy pays off when a second low follows the track of the first when we have only 350 nautical miles to go. This time, we were far enough south that we’re able to keep the winds on the stern throughout the gale. We arrive at Canal de Chacao just as the wind from this second gale begins to ease, and we drop anchor on October 16, just after midnight, concluding a 24-day passage.

The U.S. Coast Guard is asking all boat owners and operators to help reduce fatalities, injuries, property damage, and associated healthcare costs related to recreational boating accidents by taking personal responsibility for their own safety and the safety of their passengers. Essential steps include: wearing a life jacket at all times and requiring passengers to do the same; never boating under the influence (BUI); successfully completing a boating safety course; and getting a Vessel Safety Check (VSC) annually from local U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, United States Power Squadrons(r), or your state boating agency’s Vessel Examiners. The U.S. Coast Guard reminds all boaters to “Boat Responsibly!” For more tips on boating safety, visit www.uscgboating.org.