Red-blooded, burger-eating, truck-driving American billfish hunters love power; the more the better. Believe it or not, there is such a thing as too much power. Take, for instance, a billion volts of electricity surging through your boat’s electrical systems at 60,000 miles per second. Ouch.

Lightning is one of the most massive displays of unrestrained raw power that any of us is likely to experience at sea, and when encountered up close and personal, the danger is significant, to say the least. It can fry every electrical item on your boat, trigger an explosion or fire, blow holes in your hull sides, and leave you dead in the water. That’s the bad news. What’s the worse news? Lightning is so unpredictable that there’s no 100 percent safe way to prepare for and defend against it. You can, however, tilt the odds in your favor when lightning strikes.

Zap and Trickle

Lightning is created when updrafts bring super-cooled water droplets and ice crystals together, and clouds become electrically charged and generate current. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, although there are plenty of theories on the table, no one can say for sure exactly how this interaction between ice crystals creates a charge. But we do know that this charge forms an electrified channel of particles called a stepped leader, which zigzags through the air along the path of least resistance, in jagged segments about 50 yards long.

The stepped leader itself is actually invisible, since it shoots along faster than the human eye can register. As the stepped leader nears a channel of opposing electrical charge — which can take the form of a tree, pole, building or boat — the two channels connect and the juice begins flowing to the tune of 100 million to 1 billion volts and billions of watts. What we actually see is the flash of one to 20 return strokes, brimming with power and yet just an inch or two in diameter.

Much as a lightning rod on a house or building works to guide the power to ground on land, the key at sea is to give all of that electricity somewhere to go. Remember, it’s merely following the path of least resistance — so give it one of your choosing, instead of leaving its path entirely to chance.

One thing must be made perfectly clear again — there’s no 100 percent safe solution to lightning. Its unpredictability and sheer power are so overwhelming that the best we can hope for is to reduce the chance of damage occurring from a strike. Your first and best line of defense is to avoid electrical storms in the first place. Track the direction of the storm’s progress with your radar, and don’t wait until it’s right on top of you to start moving.

If you hear a hissing sound coming from your antennae, outriggers or fishing rod tips, you’ve probably waited too long. Lightning can strike up to eight or 10 miles away from the actual storm.

Cage the Beast

The most common form of lightning preparedness on boats comes in the form of a zone of protection. The “zone” is formed by grounding bonded metal structures that surround an area above head level to attract and carry a lightning strike to ground via the water. Most commonly on a boat, the electricity travels down and into the water either through the engines to the shafts and props, or through a separate external bonding plate. While this usually protects you and your passengers from getting fried, it can, unfortunately, also cook your engine’s sensors, monitors and/or computer controls after absorbing a strike.

A properly bonded boat may already have this form of lightning protection built in to some degree. Unfortunately, that degree can vary quite a bit. And according to Dr. Ewen Thomson, CEO of Marine Lightning Protection Inc., that degree is probably quite low. “Most manufacturers build with little or no regard to lightning,” he says. “And, unfortunately, major retrofitting is usually necessary to install a lightning protection system properly.” That means bonding and connecting all of those metal parts to complete the zone of protection.

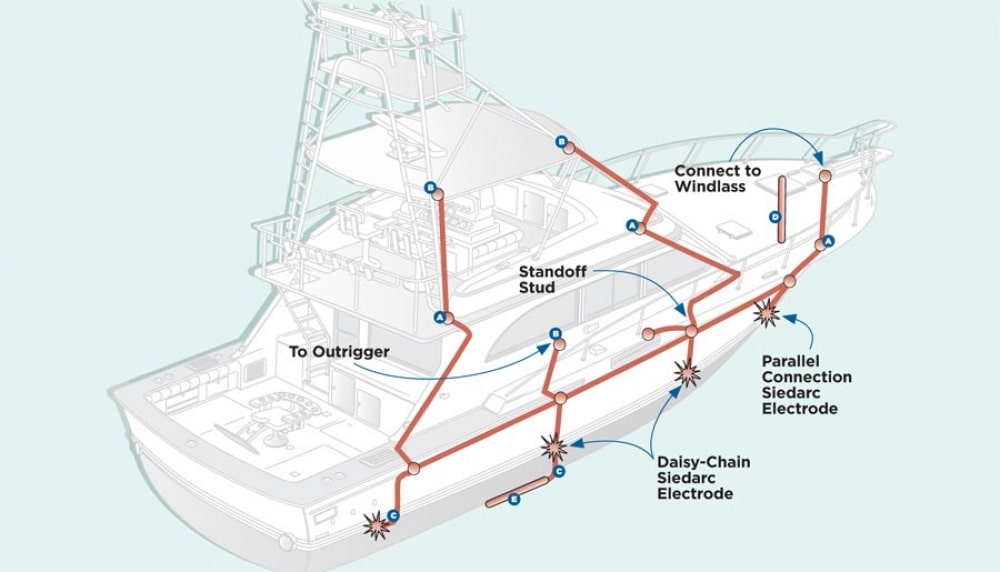

“A sport-fishing boat is great to work on,” Thomson explains, “because you have a lot of metal to work with, and outriggers, which can always be regarded as lightning rods. And with the superstructure and rails found on fishing boats, once you tie them all together, you usually just need to add a conductor around the stern. You’ve created a large zone of protection.”

Distributing the lightning’s energy into the water through multiple sources is key. It helps prevent side flashing. When there’s too much power to pass along a single path, and the lightning jumps from one conductive item in your boat to another, that’s called side flashing. Lightning can jump right through bulkheads, furniture or even people as it flashes from point to point. So, providing electricity with additional exits of your choice is very important.

There are several ways to try and get the power to go where you want it to go. “You can add grounding strips outboard of the props, and you can also use bronze rudders as underwater grounds,” Thomson says. Or you can add electrodes, like the Siedarc, which Thomson’s company sells. These fit into through-hulls placed just above the waterline, providing multiple exit points for a charge.

Static dissipaters are also helpful. They use multiple discharge points (thin metal filaments that look, more or less, like a big wire brush) to rapidly dissipate a charge into the atmosphere. That greatly reduces the object’s electrical “attractiveness,” which lessens the chance of a strike occurring in the first place. They’re inexpensive and easy to add to any boat; however, while they’ve proven effective at reducing strikes on telecommunications towers, their effectiveness on boats hasn’t been confirmed. Their overall usefulness on boats is called into question by many experts; yet both the U.S. Coast Guard and Navy find them effective enough to employ them on many of their vessels.

Stream inhibitors present another option. Though there aren’t any studies supporting their use on boats in particular, these units have been proven effective in the lab. They reduce the chance of lightning striking an object by inhibiting the formation of streamers from the structure, via glow mode corona, which is essentially a natural electrical discharge. They’re easily mounted and don’t require a major retrofit.

There simply is no such thing as complete protection against lightning. But with some good judgment and a little retrofitting, you can greatly reduce the probability of your boat being struck and damaged — or worse — when nature unleashes her power.

Lightning Tip

Since no form of lightning preparedness is 100 percent, you should take all measures possible when being struck seems likely. One unusual trick is to take all of your handheld electronic units into the galley. “An oven, especially a microwave, is an enclosed conductor,” Dr. Thomson explains. Put your handheld devices inside, close the door, and they should be safe from the strikes — just don’t accidentally press the Start button.

The U.S. Coast Guard is asking all boat owners and operators to help reduce fatalities, injuries, property damage, and associated healthcare costs related to recreational boating accidents by taking personal responsibility for their own safety and the safety of their passengers. Essential steps include: wearing a life jacket at all times and requiring passengers to do the same; never boating under the influence (BUI); successfully completing a boating safety course; and getting a Vessel Safety Check (VSC) annually from local U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, United States Power Squadrons(r), or your state boating agency’s Vessel Examiners. The U.S. Coast Guard reminds all boaters to “Boat Responsibly!” For more tips on boating safety, visit www.uscgboating.org.