Sixteen days after leaving the Galápagos for French Polynesia, I was woken up in the middle of the night by my partner, Guillaume Perret. Only this time we weren’t changing shifts. Even half asleep, I knew something was wrong. Rebelle, our Philippe Briand-designed Kelt 30-foot sloop, was rolling wildly and had turned broadside to the waves.

Our passage up until that night had been going smoothly. We’d had steady, 20-knot winds and were averaging 160 miles a day. With any luck, we’d make landfall in French Polynesia in good time. But our luck took a turn for the worse on Day 16. At noon, an accidental jibe caused the boom to snap in two. At midnight, things got a whole lot worse. Conditions had deteriorated, and Guillaume was at the helm when the rudder sheered off. It quickly floated out of reach and out of sight. We were 650 miles from land and completely unable to control the boat.

Were we taking on water? We emptied the back cabin quickly and confirmed that it was dry. Once the adrenalin from our initial panic subsided, we had to come up with a plan. We’d seen pictures of a jury rig that used a spinnaker pole and a wooden board that was attached to the backstay and controlled with lines led to the cockpit winches. We’d start building such a rig at first light.

Since we didn’t have any spare plywood with us, we used two locker doors to make the rudder. We bolted the doors together, lashed them to the end of our second spinnaker pole (the first one was being used as our new boom), led lines to the primary winches, and attempted to steer. The makeshift rudder kept jumping out of the water in the waves, so we attached diving weights to hold it down.

Steering with this rig was a lot harder than we thought it would be. We tried using the engine to help us steer and the triple-reefed main to keep us stable, but as soon as we managed to turn downwind, the boat would immediately round back up. We couldn’t keep on a straight course, and we soon realized that our fix wasn’t going to work. In hindsight, we could’ve lowered the mainsail completely, used the headsail to hold us on course, and towed warps behind us to keep the boat headed downwind. And steering with the sails-balancing the heavily reefed main and the jib-may have been the best solution. But we didn’t try those techniques.

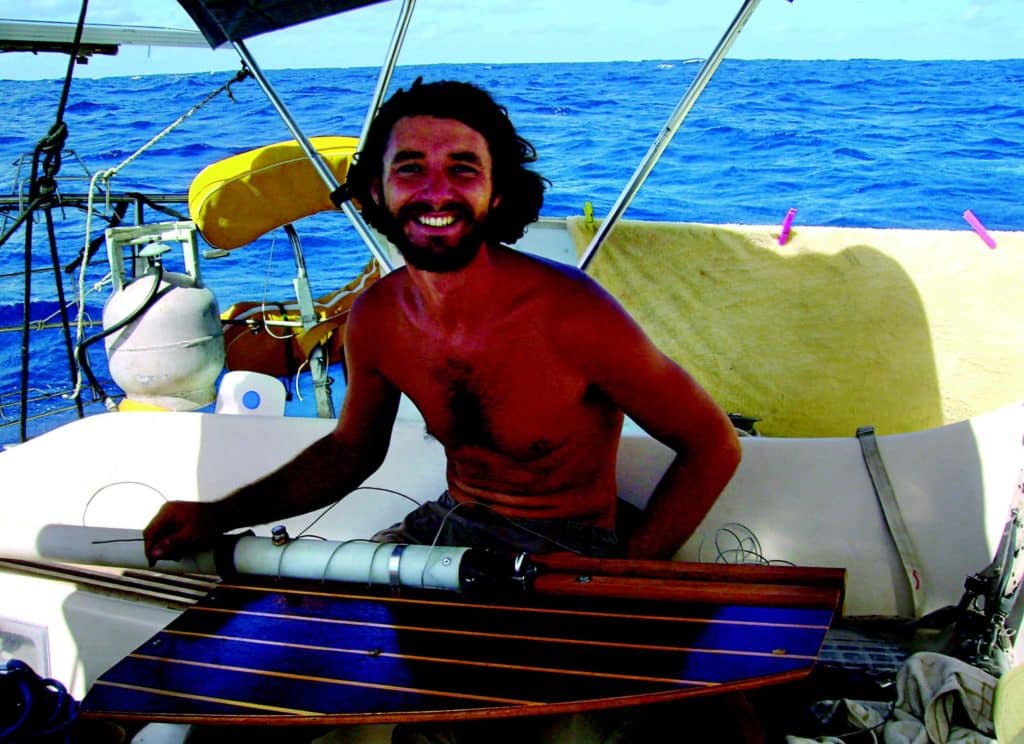

The following morning, Guillaume decided to dive to check out what was left of the rudder and to see if he could find a better solution. Going into the water in the open ocean is risky, but we had to do something. He tethered himself to the boat, went under with a mask and snorkel, and came up smiling. The rudder had broken away, but a portion of the rudderstock and a portion of a stainless-steel rudder reinforcement remained. With a bit of luck, it might just be strong enough to hold a temporary rudder for the next 650 miles.

We slowly lowered the broken stock out of its tube, and Guillaume retrieved it from the water. Once we had the stock on deck, we lashed the plywood locker doors around the steel bar as securely as we could to make the new rudder.

Then came the hard part: reinserting the rudderstock back into its tube from the water. We attached a line to pull and guide the stock into place from the cockpit. The buoyant rudder floated, so we attached weights to sink it just enough for Guillaume, in the water, to line it up with the entrance of the rudder tube.

It was incredibly nerve-racking to watch Guillaume diving under the stern of boat, but he did the job unscathed. With our newly fabricated rudder in place, three reefs in the main, and a small amount of headsail out, we were able to turn downwind with enough steerage to allow us to set a course again for the Marquesas.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before our new rudder broke away. And because we hadn’t tied a safety line to it, we lost it, too. The good news was that we’d managed to sail 60 miles in the right direction. The bad news was that we still had a long way to go and were, once again, adrift.

Now we needed another rudder and a replacement stock. Unfortunately, we were all out of locker doors, so we were left scanning the boat for another usable wooden surface. How about the teak and holly floorboards? As for the new stock, we used the second spinnaker pole. Luckily, it was almost the right diameter to fit into the rudder tube; it was just a hair too small. The plastic tubes that held our paper charts turned out to be exactly the right size to fit over the spinnaker pole and fill the gap perfectly. We strengthened the thin aluminum pole by filling it with strips of wood and steel and packed out the remaining air spaces with anything we had-even rice from the galley-in hopes of making our new stock as solid as possible.

We waited until the sea was at its calmest the next day for Guillaume to go into the water and slide the new rudder and stock back in place. Then we attached the original tiller and were ready to go. The big question: Would it hold?

The first few minutes at the helm felt like hours. We felt the force of each wave on our dangerously fragile structure, and we knew that if this attempt failed, we could be in real trouble. With the waves far too big to set the self-steering, we hand steered in shifts. We still had hundreds of miles to go, but we were finally moving in the right direction. Steering required intense concentration to minimize the force on the rudder as we surfed down the waves, but nervous adrenaline-and knowing that one mistake would leave us adrift-kept us going. Over the next six days, we encountered up to 35 knots of wind. We trailed a light anchor and some thick ropes to help control the boat and to take some pressure off the rudder. Still, we did 8 knots at times. We were definitely making progress toward Nuku Hiva, in the Marquesas. Fatigue set in, and while we experienced huge emotional ups and downs, we continued to work together. Knowing that we weren’t totally alone-we had radio and email contact with the local authorities on land and with other boats-lifted our spirits, but we felt that we had to solve the problem ourselves. And that’s what makes offshore sailing so satisfying. We faced a serious challenge and overcame multiple setbacks, but thanks to our rice-packed rudderstock and our cockpit-sole rudder, we sailed ourselves safely to Nuku Hiva in six days.

The U.S. Coast Guard is asking all boat owners and operators to help reduce fatalities, injuries, property damage, and associated healthcare costs related to recreational boating accidents by taking personal responsibility for their own safety and the safety of their passengers. Essential steps include: wearing a life jacket at all times and requiring passengers to do the same; never boating under the influence (BUI); successfully completing a boating safety course; and getting a Vessel Safety Check (VSC) annually from local U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, United States Power Squadrons(r), or your state boating agency’s Vessel Examiners. The U.S. Coast Guard reminds all boaters to “Boat Responsibly!” For more tips on boating safety, visit www.uscgboating.org.