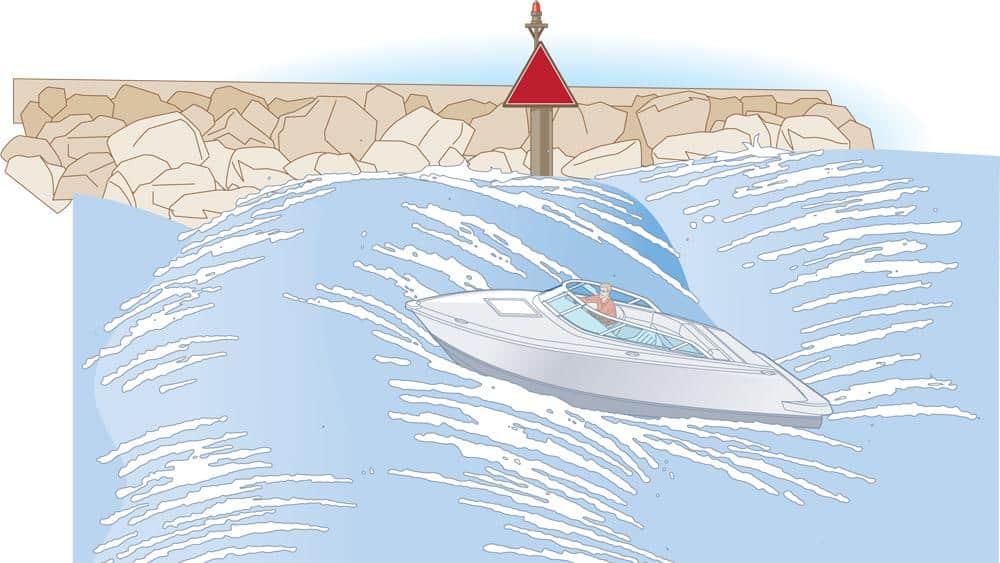

You’ve read it before. When coming through a breaking inlet, stay on the back of a wave and keep the boat straight. If you accelerate over the crest you could pitch-pole or broach; slow down, and the breaker behind might dump into your boat. Good advice. But there’s more to navigating a breaking inlet than any single canon can explain.

Like most boat-handling skills, this one requires the twofold ability to see what’s going on in the environment and to predict the consequences of several sequences of action. Always leave yourself an “out.”

Developing your peripheral vision can help you see what’s going on. Speed-reading, living in a bad neighborhood and participating in sports all enhance peripheral vision. But you can simply practice looking for things out of the corner of your eye. While you’re running an inlet, peripheral vision can alert you to the errant timber you must dodge or to a crest abeam of your boat and running parallel to your course, a crest that could suddenly change direction and lash out at you.

I’ve seen waves that broke in a 180-degree pattern. Charging forward, humping up white, they shifted suddenly parallel to shore, then shifted again, expending their energy seaward onto the very bar that spawned them. Big-moon currents or storm surges can create this scenario, especially over the ever-shifting bottom of many inlets. When it happens, part of an old dogma applies: Keep the boat straight — except in this case, straight is a relative term, one that can change moment to moment as you stay stern-to the breaker chasing you while trying not to run inside the curl of another wave that’s decided to veer.

Do you race forward and risk stuffing the bow in the trough ahead? Is there time between waves to throttle back and let the anomaly pass ahead without getting pooped? Such vagaries caused sailors of old to invent sea monsters, and we modern seafarers to recount jokes ending with the punch line “Please hand me my brown trousers.”

If you like, substitute “keeping on your toes” or “keeping your head on a swivel” for sight. It’s better, though, to have applied vision, which I’ll define as the ability to process what sight tells you and to make decisions in advance of that position between Messrs Rock and Hardplace.

Approaching from offshore, you see a band of white where the cut’s supposed to be. It’s breaking, and breaking big. Closer now, you see gaps in the froth. The water is deeper in these gaps, which allows most waves to pass without breaking, or breaking as hard. You watch, perhaps slowing or stopping to find a pattern in the sets. The safest route envisioned, you keep the boat straight and on the back of a wave. And you keep your head on a swivel.

The U.S. Coast Guard is asking all boat owners and operators to help reduce fatalities, injuries, property damage, and associated healthcare costs related to recreational boating accidents by taking personal responsibility for their own safety and the safety of their passengers. Essential steps include: wearing a life jacket at all times and requiring passengers to do the same; never boating under the influence (BUI); successfully completing a boating safety course; and getting a Vessel Safety Check (VSC) annually from local U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, United States Power Squadrons(r), or your state boating agency’s Vessel Examiners. The U.S. Coast Guard reminds all boaters to “Boat Responsibly!” For more tips on boating safety, visit www.uscgboating.org.