In my years as an adventure journalist I’ve written about plenty of amazing journeys. There was Aleksandr “Olek” Doba, who paddled a kayak across the Atlantic three times in his sixties and seventies. Randall Reeves, who sailed a figure-eight around Antarctica and through the Northwest Passage, because just circling the globe wasn’t enough. And of course “Adventure Aaron” Carotta, who canoed the length of the Missouri-Mississippi river system, then decided to cap it off by rowing around the world in a 23-foot rowboat he calls Smiles.

He made it as far as the central Pacific, to a spot not far from where the whaleship Essex went down 203 years ago. That distressing tale—the real-life inspiration for Moby Dick—involved an angry whale and one of the most harrowing survival stories of all time. Rescuers found two haggard survivors 94 days later, “sucking the bones of their dead mess mates, which they were loath to part with.”

What a difference a couple of centuries makes.

Aaron’s epic ended with a hot shower and steak dinner aboard a passing oil tanker and was notable only because he waited a month to activate his personal locator beacon (PLB), a device the size of a deck of cards that can help rescuers find someone anywhere on the planet.

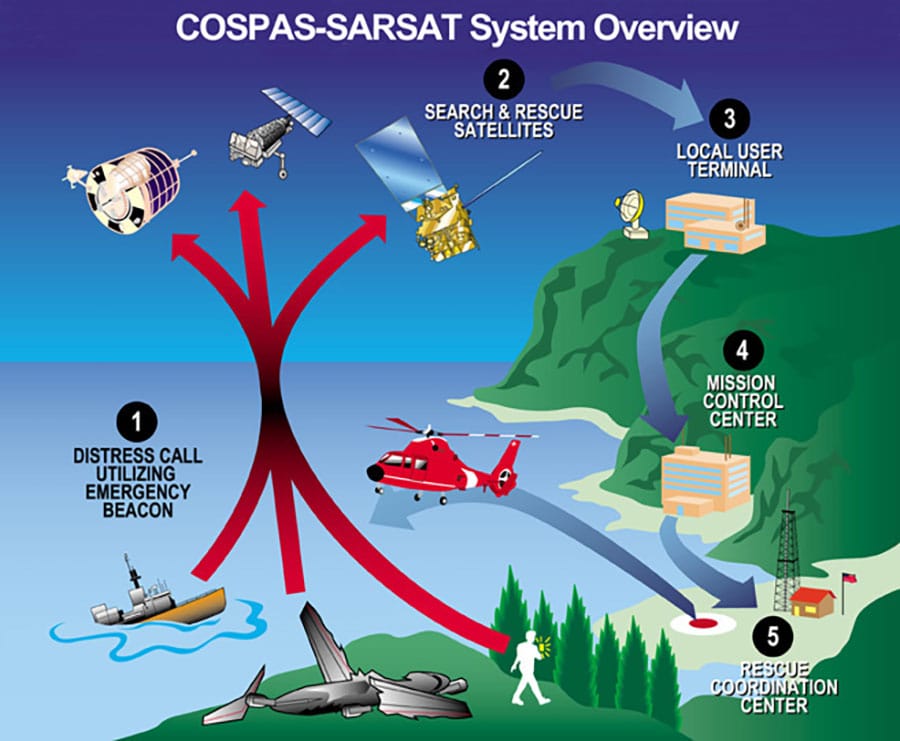

PLBs and the similar Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons (EPIRBs) work by transmitting distress signals to a network of satellites orbiting the earth. The satellites are part of the Cospas-Sarsat system, a global search and rescue network that can quickly detect and locate signals from PLBs and EPIRBs.

When a satellites picks up a distress signal from a beacon, it relays the information to a global mission control center, where authorities can quickly determine the beacon’s location and dispatch rescue teams to the area. Since the first Cospas-Sarsat satellites were launched in 1982, the system has aided in the rescue of more than 46,000 people.

As U.S. Coast Guard search and rescue specialist Scott Talbot puts it, beacons “take the search out of search and rescue.” Talbot, who oversees Coast Guard rescue operations in the Gulf of Mexico and the inland waterways of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers systems, says carrying a PLB or EPIRB is the number-one thing boaters can do to make his job easier.

PLBs and EPIRBs are close to foolproof as long as you remember to register your beacon so its unique signal will tell search and rescue crews not just where to find you, but also who you are, and the name of a friend or loved one to contact if the beacon is activated. This helps rescuers find you, and also helps them quickly tell false alarms from life-and-death emergencies.

Beacons are not just for offshore boaters either. Talbot says many of his teams’ search and rescue missions take place on inland waters – boaters who experience emergencies in the maze of sloughs and bayous of the lower Mississippi, or who just get into a pickle on their way back to the marina. PLBs are a crucial tool for boaters, pilots, hikers and backcountry skiers alike, providing peace of mind and a critical lifeline in case of an emergency.

And did I mention you can pick one up for less than $400?

Do One Thing, and Do It Well

PLBs are designed to do one thing: summon help in an emergency. That sets them apart from other communication devices popular with boaters and adventurers, such as satellite trackers. Aaron carried a PLB with him in the Pacific, but his go-to communication tool was his Spot GPS tracker, a satellite-enabled device that sends regular position updates and can be used for text messaging.

The Spot tracker has a rechargeable battery that’s good for about 10 days, which became a problem when the solar power setup in Aaron’s rowboat went on the fritz a few weeks after he left the Galapagos islands. The tracker was set to send automatic position updates to Aaron’s website, so when he turned it off to conserve power friends following his journey feared the worst. They quickly organized a search, but without the tracker’s regular position updates they could only guess where Aaron was and hope he was alive.

Aaron plugged along this way for four more weeks. In his words he was traveling blind, steering only by compass as the unfortunate crew of the Essex had two centuries before. But he had a strong hull beneath him, a good water-maker and plenty of provisions.

“I just kept rowing,” he said. “Like, ‘no problem. I’m in a rowboat. I got this.’” A spiritual man, he reasoned that if Jesus had spent 40 days alone in the desert, he could last the same at sea. Forty days was coincidentally about how long he thought it would take him to reach the nearest island group, the Marquesas. So he kept chugging.

Then, 33 days after losing contact, a rogue wave rolled his little rowboat. Smiles was designed to right herself, but the hatch to the tiny cabin was open, and the boat quickly filled with water. Aaron had just enough time to swim to the surface and clamber into his inflatable life raft. Fearing that Smiles would soon go down and take the raft with it, he cut the tether. As he drifted some 1,400 miles northeast of Tahiti, Aaron took stock of his possessions: One pair of board shorts, and the PLB.

He lifted the safety guard and pressed the button. Within hours a plane flew overhead, the first he had seen in 80 days at sea. As it drew nearer Aaron could make out the orange and white livery of the U.S. Coast Guard. The plane was almost at the limit of its range, and soon returned to base to refuel. Aaron spent the night bobbing in rough seas, bailing water and battling the cold by curling into a ball on the life raft’s floor.

The next day, a merchant ship that had been alerted to his position by the Coast Guard pulled up alongside his raft. Its crew hoisted him aboard with a crane. They fed him, gave him clothes and a warm bed and, a week later, dropped him off in Honolulu.

All thanks to his PLB.

The U.S. Coast Guard is asking all boat owners and operators to help reduce fatalities, injuries, property damage, and associated healthcare costs related to recreational boating accidents by taking personal responsibility for their own safety and the safety of their passengers. Essential steps include: wearing a life jacket at all times and requiring passengers to do the same; never boating under the influence (BUI); successfully completing a boating safety course; and getting a Vessel Safety Check (VSC) annually from local U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, United States Power Squadrons®, or your state boating agency’s Vessel Examiners. The U.S. Coast Guard reminds all boaters to “Boat Responsibly!” For more tips on boating safety, visit uscgboating.org.